-

Biography

Erkki Veltheim (b. 1976 Finland) is an Australian composer and performer. His practice spans noise, audiovisual installation, improvisation, notated music, electroacoustic composition, pop arrangements and cross-disciplinary performance.

Erkki has been commissioned by the Adelaide Festival, Vivid Festival, Australian Art Orchestra, Sydney Symphony Orchestra and Musica nova Helsinki, and his works have been performed by groups such as the London Sinfonietta, defunensemble, Melbourne Symphony Orchestra and Sydney Symphony Orchestra. He composed the orchestral works for celebrated Australian indigenous musician Gurrumul's posthumous album Djarimirri, which won 4 ARIA Awards and the 2018 Australian Music Prize. In 2019 he released 'Ganzfeld Experiment' for electric violin and audiovisual processing on the avant-garde label ROOM40, a work described by The Quietus as 'an exquisite form of mysticism'. His work has also been released on legendary Swiss label Hat Hut and close collaborator Anthony Pateras's label Immediata.

Erkki's cross-disciplinary projects include audiovisual performance work Another Other (2014/2016), with co-creators Anthony Pateras, Natasha Anderson and Sabina Maselli, commissioned by Chamber Made Opera, and audiovisual installation Fusion of Tongues (2015), commissioned by Punctum and La Maison Folie, Belgium, for ‘Mons 2015 – European Capital of Culture’ program. His film soundtracks include 'Gurrumul' (dir. Paul Williams) and 'The Song Keepers' (dir. Naina Sen), both featured at the 2017 Melbourne International Film Festival (MIFF), and the short film 'Landing' (dir. Sabina Maselli), featured at the 2019 MIFF.

Erkki was the arranger and Musical Director for 'Bungul' (2020 Sydney, Perth and Adelaide festivals), and 'The Genius of John Rodgers' (2019 Queensland Music Festival). He has also created arrangements for artists such as Tom E Lewis, Kate Miller-Heidke, Archie Roach, Alice Skye, Rayella, Emily Wurramara, and Zulya.

Erkki has performed with the Australian Art Orchestra, Australian Chamber Orchestra, Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, Elision and Ensemble Modern and Ensemble musikFabrik, and is a member of the improvising trio North of North with Scott Tinkler and Anthony Pateras. He has also played with many musicians from a wide range of styles and backgrounds, including Chris Abrahams, Mark Atkins, Bae Il Dong, William Barton, Han Bennink, Anthony Burr, Cat Power, Clocked Out, Brett Dean, Robin Fox, Paul Grabowsky, Shane Howard, Mike Patton, Stephen Pigram, Jon Rose, Wadada Leo Smith and Amanda Stewart.

Erkki is a recipient the Melbourne Prize for Music 'Distinguished Musicians Fellowship 2019' and a 2013 Myer Creative Fellowship, as well as multiple Australia Council and Creative Victoria grants. He was an Artistic Associate of Chamber Made Opera between 2013-2016.

- |

- CV

- |

-

Contact

N: Erkki Veltheim

E: erkki.veltheim@gmail.com

W: http://erkkiveltheim.com

T: +61 407 328 105 - |

-

Imprint

- Menu = https://erkkiveltheim.com

- Shell = https://erkkiveltheim.com

- Windows = https://erkkiveltheim.com

- Anthony Burr

- |

- Anthony Pateras

- |

- John Rodgers

- |

- Marc Hannaford

- |

- Sabina Maselli

- |

- Scott Tinkler

- A Faraway Landscape (at dusk)

- |

-

Dead Ringers

-

Text = dead_ringers_note.md +

Dead Ringers (2017) takes its inspiration from bird mimicry and mimesis, ie. the representation of the natural world in art and culture. It is scored for 2 harmonicas, flute, violin, cello, electric guitar, percussion and tape, and was commissioned by Tura New Music for the Narli Ensemble. The tape part consists of slowed down recordings of film rolling through a projector, the archetypal mimetic machine, and Finnish bird calls from the 1960s, which, when slowed down, bear an uncanny resemblance to tropical Australian bird calls. The instrumental ensemble construct their own synthetic 'bird calls' from limited pitch materials, creating a simulated dawn chorus as a counterpoint to the prerecorded tape part.

-

Text = dead_ringers_note.md +

- |

-

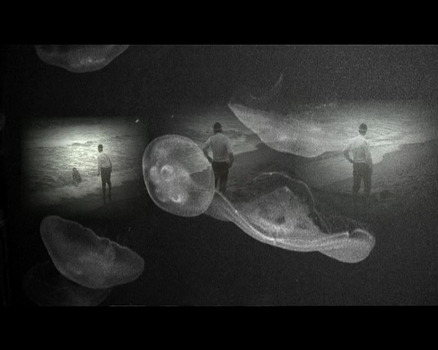

Ganzfeld experiment

-

Text = ge_note.md +

GANZFELD EXPERIMENT

'Ganzfeld experiment' is an audiovisual work for electric violin, video and signal processing. In parapsychology, a Ganzfeld experiment is a test for evidence of extrasensory perception, particularly telepathic communication. It is based on the Ganzfeld (German for 'total field') effect, which describes the tendency of our central nervous system to invent patterns in random, uniform sensory data, for instance hearing voices in white noise or seeing images in visual static. In a Ganzfeld experiment, a test subject is exposed to such a continuous uniform stimulus field, while another person attempts to send them telepathic messages. My work replicates elements of this experiment in order to explore synaesthetic hallucinations, the electric violin signal gradually manipulating and transforming static noise in both the audio and visual domains. This work is also influenced by esoteric and occult numerology, Tony Conrad and Brion Gysin’s experiments with flicker and the Dreamachine, and Terry Riley's ‘Persian Surgery Dervishes’, which fuses composition with improvisation in a long-form ecstatic, trance-like work. The audio and video processing is done in Max/Jitter with a patch that combines predetermined and random elements.

I’m always interested in how structure interacts with randomness, form with formlessness, and ways in which sound can be used to transform a listener’s perception and sense of time and place. I’m also often looking for ways to expand my musical ideas to other media, through ritual, installation, or visual elements. An important motive in my work is the idea that through sound (and these other elements) we can enter different realms of experience: the mystical, the magical, the shamanistic. In ‘Ganzfeld experiment’, as in many other of my works, I’m particularly searching for an ecstatic experience, one that transports the audience outside of their rational, everyday selves. The constantly panning white noise and visual flicker are intended to induce a hallucinatory state where one’s sense of time and perception are disoriented, becoming prone to suggestibility by the repetitive but subtly morphing sounds and images.

-

Audio = ge_excerpt_1.mp3

-

Audio = ge_excerpt_2.mp3

-

Audio = ge_excerpt_3.mp3

-

Audio = ge_excerpt_4.mp3

-

Text = ge_note.md +

- |

-

Prelude and Coda: a seance for an orchestral concert

-

Text = pc_note.md +

'Prelude and Coda: a seance for an orchestral concert' plays with the literal/etymological meanings of these words (ie. prelude = before playing, coda = tail, seance = sitting, etc.), as well as the inner/outer worlds that are the theme for the concert. It's kind of a ritual to contact the spirit of Schoenberg to try to convince him to reverse his development of the Twelve-tone method, which for me symbolises the sacrifice of genuine exploration of inner worlds (the irrationality of the human mind/emotions) for the superficial rationality of a strict system of composition. It also pays tribute to the Minotaur legend, the labyrinth being a journey into that animalistic centre of our being that every now and then rears its head, sometimes ugly, sometimes beautiful...

The instrumentation is:

- picc, ob, eb cl, contrabass cl, contrabsn

- 2 hn, tpt, tbn

- 2 perc

- piano/celeste

- harp

- strings (1.1.1.1.1)

In the first movement, 'Prelude', the idea is that the string quintet is already on stage playing (with practice mutes) an arrangement/extension of Schoenberg's 'Praeludium' from Op.25 (chronologically his first dodecaphonic piece), and keeps playing this throughout as an independent unit.The winds, brass and percussion (except the oboe) are arranged behind the audience in a semicircle, and Brett will be conducting them 'over' the audience, ie. facing them with the audience between him and them. There will be a percussion instrument made of 2 corrugated iron sheets on sawhorses (my percussion instrument of choice...), which will be played with hammers, an electric drill, and saw as well as more standard beaters. The oboe, piano and harp will be on stage and will intermittently play short interjections against the rest of the ensemble. Their role is to play different voicings of the musical letters drawn from Schoenbergs initials, ie. A, S (es = Eb), C, H (= B). This musical autographing is an old trick of course; in my piece this repeated chord is meant to invoke his ghost in order to call him to task over serialism. The oboe plays repeated microtonal As around 440Hz, signalling this instruments role in tuning the orchestra, a prelude to any orchestral concert. The microtonal variations are a reference to the kind of mechanics Im using for the compositions structure, being based on the Magic Square of the Sun number square, which is made up of the first 36 integers and adds up to 666, and some recordings (or renderings) of the sound of the sun. The use of these are obliquely related to the idea of the Minotaur, as a symbol of the sun god, and the architect of the labyrinth, Daedalus, whose son Icarus of course flew too close to the sun. These elements are not really meant to cohere into a neat narrative, theyre more of an inspirational web of associations for the work, in a similar way that in many rituals, divergent elements are put into orbit around a unified set of actions in order to elicit a certain associative link between them and access a kind of transformative experience or consciousness.

The second movement, 'Coda', will have the whole ensemble on stage apart from one percussionist who will play the corrugated iron installation with cello bows, most likely amplified with contact microphones. The movement will be based on a simple concept of attack and decay (the 'tail' of the attack), being a series of 37" unevenly spaced chordal/percussive loud attacks followed by different kinds of sustained trails of sound, all based on the material from the 'Prelude'. The celeste and harp will play 'remnants' of the Schoenberg 'Praeludium' in the background. I think of these as the 'entrails' of Schoenberg's piece, recalling the practice of divination from the inner organs of sacrificed animals.

-

Audio = PC_Prelude.mp3

-

Audio = PC_Coda.mp3

-

Text = pc_note.md +

- |

-

Continuity hypothesis

-

Text = continuity_hypothesis_note.md +

The Continuity Hypothesis is composed for bass flute, bass clarinet, cello, digital keyboard and electronics. The work's name is borrowed from linguistics, where the 'continuity hypothesis' is concerned with an infant's first language acquisition, specifically investigating whether linguistic structures are innate or learned progressively through acquiring vocabulary. For me the interesting aspect of this research is whether a baby's babbling is genuine linguistic activity or merely physical training of the vocal tract anatomy. In other words, is a baby expressing their thoughts and feeling through babbling, or is it merely impulsive muscle activity?

In my work, the acoustic instruments, whose range is roughly similar to that of humans, interpret notes and instructions that allow for some improvisation, creating their own rhythmic and melodic motives from the given materials. The pitch materials are derived from the composer Fritz Heinrich Klein's 'Mother Chord', and the rhythmic materials are based on the relative lengths of consonant and vowels, and the rate at which these are introduced in a typical infant's vocabulary.

The keyboardist plays any extracts from J.S.Bach's 'Well-tempered Clavier', which were originally composed as a pedagogical aid to teach the student to play in all the 12 major and minor scales, a relatively recent invention at the time. This collection, for me, symbolises a kind of 'universal language' that haunts Western classical music to this day. The sound of the keyboard in my piece is muted, and instead the keys control the live signal processing of the electronics, combining Bach's highly ordered compositions with an element of chance in how they activate the processing. This processing, created on the software 'Max', samples and filters the acoustic instruments, akin to a child's parent who repeats a baby's utterings, guiding them through positive feedback towards language competence.

The live music is accompanied by a tape part created from the sounds of film projectors, a mechanical rhythmic polyphony that situates the musicians inside an imaginary factory to forge a possible new language from bygone raw materials.

This work was composed at the request of Andre de Ridder for Finland's defunensemble, and was premiered by them at Musica Nova Helsinki in February 2017.

- Score = continuity_hypothesis_score.pdf

-

Audio = continuity_hypothesis_defun.mp3

-

Audio = Continuity_Hypothesis.mp3

-

Text = continuity_hypothesis_note.md +

- |

-

The Slow Creep of Convenience

- Programme = slow_creep_inland_programme.pdf

- Programme = https://inlandconcertseries.net

- |

-

Bespoke alienation

- Programme = bespoke_alienation_inland_programme.pdf

- Programme = https://inlandconcertseries.net

- |

-

ENTERTAINMENT=CONTROL

- Image = entertainment_control_01.jpg

- Programme = entertainment_control_inland_programme.pdf

- Label = https://anthonypateras.com

- Audio = https://immediata.bandcamp.com

- Programme = https://inlandconcertseries.net

- |

-

Study for a Fusion of Tongues

-

Audio = fot_inland_abc.mp3

- Programme = fot_inland_programme.pdf

- Programme = https://inlandconcertseries.net

-

Audio = fot_inland_abc.mp3

- |

- The silence of a falling star

- |

-

Two New Proposals for an Overland Telegraph Line from Port Darwin to Port Augusta, from the Perspective of Alice Springs

-

Text = tnp_note.md +

Two New Proposals for an Overland Telegraph Line from Port Darwin to Port Augusta, from the Perspective of Alice Springs

This piece is inspired by the first piano in Alice Springs, which was carried there by camel when the town was founded in 1872 as a telegraph repeater station, being roughly at the halfway point of the Overland Telegraph Line between Port Augusta and Port Darwin.

In this piece I translated the idea of the telegraph line onto the piano keyboard by utilising the fact that the distance in Hertz between the lowest and highest notes of this instrument (which has a reduced keyboard of 85 keys or 7 octaves from A0-A7) roughly equals the distance in kilometres of the Overland Telegraph Line. Metaphorically, the keyboard thus traverses a line between Port Augusta and Port Darwin, with Alice Springs being signified by the pitch Eb4. This represents the halfway point of the exponential curve that expresses the doubling of the Hertz value of each pitch on the keyboard in successive octaves. I also wanted to represent the halfway point of this distance in Hertz as expressed by a straight line, given roughly by the pitch A6, thus proposing two alternative interpretations for the placement of Alice Springs on this imaginary map.

This Hertz distance is also converted into the duration of the piece, in seconds. The original Overland Telegraph Line had 11 repeater stations along the line, which were used to manually repeat the original message, as it would weaken over large distances. I built the electronics part from the idea that the 'message' in my piece, a morse code phrase on the dyad Eb/A6 that is reiterated continuously by the piano, is similarly repeated by such 'repeater stations', through a series of delays and pitch shifts. Like the pitch (vertical domain), one series of these 'repeater stations' is based on equal divisions of the total duration (horizontal domain) along an exponential curve, and the other along a straight line. The successive pitch shifts also express these same divisions. The overall effect is a gradual fanning out of the original morse code across the entire range of the Alice Springs piano over the duration of the piece, as it reaches towards the two ends of the line, Port Augusta and Port Darwin, on both the vertical and horizontal axes.

The morse code message spells out the text of the most retweeted tweet (as reported on 13 January 2015), originally tweeted by Ellen DeGeneres on 3 March 2014:

If only Bradley's arm was longer. Best photo ever. #oscars

I wanted to use this message as I found there to be some kind of connection between the need to repeat morse messages at repeater stations across large distances and the obsessive retweeting of meaningless messages on social media. The Overland Telegraph Line revolutionised communications between Australia and the rest of the world, at the time meaning mainly London, facilitating the delivery of urgent and important messages. The rise of social media messaging represents a new kind of communication revolution, which has repurposed each one of us as a repeater station of trivial bits of information. We are now struggling not with the speed and reach of data, but rather its excessive volume, as it saturates our lines of communication in an endless and ever-accelerating cycle of self-generated regurgitation.

-

Audio = two_new_proposals.mp3

- Score = tnp_max_score.pdf

- Score = tnp_score.pdf

-

Text = tnp_note.md +

- |

-

Turing Test

-

Text = turing_test_note.md +

Turing Test was inspired by Lydia Goehr's book 'Imaginary Museum of Musical Works', which questions the concept and locus of a 'musical work'; is it contained in ideal form in a notated score, or does it exist only through a concrete performance, or is it the sum total of its performances? And how does a work of music maintain its identity across different performances? Whilst Goehr mainly dicusses examples from the notated classical canon, the basic questions can be naturally extended to improvisation, especially as it is typical in this practice for iterations of the same 'work' to sound extremely different, to the point where recognition of any common, sustained identity across these iterations becomes almost impossible. In response to this book, I became interested in constructing a piece that combines a freely improvised part with a completely automated and structurally predetermined electronic part that processes (and thus requires) this live input, creating an interdependent dialogue between an abstract structure and spontaneous live performance.

-

Audio = turing_test.x0.mp3

- Programme = turing_test_inland_programme.pdf

- Programme = https://inlandconcertseries.net

-

Text = turing_test_note.md +

- |

- FLESHEATER

- |

-

Glossolalia

-

Text = glossolalia_note.md +

Glossolalia Program note:

Glossolalia is a kind of quixotic homage to the private language games that so preoccupied the modernists of 20th Century; games that, like a candle to a moth, have always both fascinated and repelled me. This work's rhythmic material is derived from the main propositions of Wittgenstein's Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus via translation into morse code, an early and now officially obsolete mode of digital communication. In his arch-modernist treatise, Wittgenstein rages against the vagueness of language by trying to limit its scope to the binary values of truth and falsehood, but in the end falls on mystical silence to escape his logical labyrinth and find expression for the less coherent aspects of human experience. My harmonic elements are gleaned from Elliott Carter's fixation with highly isomorphic all-interval chords, an equally obsessive quest to maintain a sort of precarious balance and symmetry in the materials of communication. These rigid structures are corroded from the outset through the use of playing techniques that continuously destabilise and obscure them, as well as a gradual detuning of the top and bottom string of each instrument until they are completely slack. As the players begin to battle with the increasingly volatile and failing instruments, the musical language moves closer to a kind of involuntary onomatopoeia, resembling the sounds of concrete nature more than abstract culture. In the end it is a happy requiem, a hope that the exquisite corpse of modernism feeds maggots of a different breed; ones that embrace and celebrate the arbitrariness and uncertainty of existence rather than bracketing and analysing it.

- Score = glossolalia_score.pdf

-

Audio = glossolalia.mp3

-

Text = glossolalia_af.md +

Glossolalia

Composer: Erkki Veltheim

Commissioned: Soundstream Collective

Premiere: May 2012Glossolalia is a string quartet that is conceived of as a sort of critique of modernism from within; using elements of 20th Century modernist culture, it gradually erodes them through various playing techniques and radical detuning of the strings. It is a kind of quixotic homage to the private language games that so preoccupied the modernists of 20th Century; games that, like a candle to a moth, have always both fascinated and repelled me.

This work's rhythmic material is derived from the main propositions of Wittgenstein's Tractatus Logico‐Philosophicus via translation into morse code, an early and now officially obsolete mode of digital communication. In his arch‐modernist treatise, Wittgenstein rages against the vagueness of language by trying to limit its scope to the binary values of truth and falsehood, but in the end falls on mystical silence to escape his logical labyrinth and find expression for the less coherent aspects of human experience.

My harmonic elements are gleaned from Elliott Carter's fixation with highly isomorphic all‐interval chords, an equally obsessive quest to maintain a sort of precarious balance and symmetry in the materials of communication. These rigid structures are corroded from the outset through the use of playing techniques that continuously destabilise and obscure them, as well as a gradual detuning of the top and bottom string of each instrument until they are completely slack.

As the players begin to battle with the increasingly volatile and failing instruments, the musical language moves closer to a kind of involuntary onomatopoeia, resembling the sounds of concrete nature more than abstract culture. In the end it is a happy requiem, a hope that the exquisite corpse of modernism feeds maggots of a different breed; ones that embrace and celebrate the arbitrariness and uncertainty of existence rather than bracketing and analysing it.

-

Interview = af_dudley.mp3

- Text = https://adelaidefestival.com.au

- Report = https://realtimearts.net

- Interview = https://radio.adelaide.edu.au

-

Text = glossolalia_note.md +

- |

-

Tract

-

Text = tract_note.md +

Tract is a work for 15 instruments that is intended to be performed alongside the manikay Djupalwarra (song cycle Wild Blackfella) by the Young Wägilak Group from Ngukurr, Arnhem Land, led by Benjamin Wilfred, with the optional addition of an improviser. The idea for a work that combines traditional Aboriginal songs and contemporary Western instrumental music came from Paul Grabowsky. My solution to the obvious challenges in such a combination was to compose a self-contained work that doesn't attempt to co-ordinate its material directly with the given manikay. Rather, I have adopted some of the more perceptible musical processes employed in this song cycle, such as repeated descending lines embellished with improvised melismata, as the point of connection between the two musics. In my realisation, the higher voices of the ensemble reiterate these descending lines, while the lower voices invert this pattern. The three sections of the ensemble (strings, woodwind, percussion/piano) traverse the same basic material, but at different internal tempi and with different pitch divisions. This reflects the inexact repetition employed by the Young Wägilak Group in their singing, as well as the overriding conceptual metaphor for this work; 'tract' understood both as a stretch of land/time as well as a religious text, explored in ever finer detail to gain deeper knowledge of the material and spiritual fabric of our surroundings. My inclusion as an improviser in this performance is intended to provide a link between the ensemble and the Young Wägilak Group, with whom I have worked for several years as a member of the Australian Art Orchestra's Crossing Roper Bar project.

- Image = 3479_reid_londonsinfonietta.jpg

- Score = tract_full_score.pdf

-

Audio = tract_malthouse.mp3

-

Text = tract_note.md +

Tract is a work for 15 instruments that is intended to be performed alongside the manikay Djupalwarra (song cycle Wild Blackfella) by the Young Wägilak Group from Ngukurr, Arnhem Land, led by Benjamin Wilfred, with the optional addition of an improviser. The idea for a work that combines traditional Aboriginal songs and contemporary Western instrumental music came from Paul Grabowsky. My solution to the obvious challenges in such a combination was to compose a self-contained work that doesn't attempt to co-ordinate its material directly with the given manikay. Rather, I have adopted some of the more perceptible musical processes employed in this song cycle, such as repeated descending lines embellished with improvised melismata, as the point of connection between the two musics. In my realisation, the higher voices of the ensemble reiterate these descending lines, while the lower voices invert this pattern. The three sections of the ensemble (strings, woodwind, percussion/piano) traverse the same basic material, but at different internal tempi and with different pitch divisions. This reflects the inexact repetition employed by the Young Wägilak Group in their singing, as well as the overriding conceptual metaphor for this work; 'tract' understood both as a stretch of land/time as well as a religious text, explored in ever finer detail to gain deeper knowledge of the material and spiritual fabric of our surroundings. My inclusion as an improviser in this performance is intended to provide a link between the ensemble and the Young Wägilak Group, with whom I have worked for several years as a member of the Australian Art Orchestra's Crossing Roper Bar project.

-

Report = reid.md +

layers, exchange, simultaneities

chris reid: london sinfonietta concerts, adelaide festival

realtime 96

Tract, London Sinfonietta and the Young Wägilak Group

photo Matt NettheimTWO SUPERB CONCERTS BY THE LONDON SINFONIETTA AT THE 2010 ADELAIDE FESTIVAL ILLUMINATED SOME SIGNIFICANT DEVELOPMENTS IN MUSIC IN THE 20TH AND 21ST CENTURIES AND ESPECIALLY SHOWED HOW COMPOSERS CAN BLEND MULTIPLE MUSICAL AND CULTURAL FORMS INTO EXCITING NEW WORKS.

The first concert, titled Pacific Currents, opened with US composer Yvar Mikhashoff’s arrangement of Conlon Nancarrow’s Player Piano Study No 7, a musical revelation that set the tone for the evening. In the mid-20th century, US-born Mexican composer Nancarrow created numerous compositions by hand-cutting piano rolls for the player piano, producing works so complex they could not be performed by a single pianist, and characterised by competing rhythmic structures and layered canon forms. Mikhashoff’s realisation involves expanded instrumentation—strings, winds, brass, harpsichord, piano, celeste and percussion—and it brilliantly captures Nancarrow’s breathtaking pace and complexity while adding some extraordinary textures, drawing out the layering to produce a rapturous work.

Silvestre Revueltas’ Ocho Por Radio (1933) followed, a work for octet that evokes the music of radio in his native Mexico, especially the mariachi bands, and which combines multiple genres into a single, increasingly chaotic work. Unsuk Chin’s electrifying Double Concerto (2002) for piano and percussion blended virtuosic solo instrumentals by Lisa Moore and Owen Gunnell into a complex series of cascading musical structures that build and rebuild, drawing prepared and natural piano passages into balanced intensity with the percussion and creating a dialogue exploring all kinds of percussive sonorities. John Cage’s Credo in the US (1942), for piano, percussion and either a radio or a phonograph, was originally written as a dance piece and prefigured Stockhausen’s use of radio in performance. In this realisation, a laptop was used to supply the recorded material, including fragments of Chopin, ragtime and other popular music that dramatically contrasted with the live elements and echoed Revueltas’ concern with the cultural impact of reproduced music.

The first concert concluded with John Adams’ highly rhythmic Son of Chamber Symphony (2007), which has also been choreographed to and includes fragments of his opera Nixon in China. Though less cerebral and more accessible than preceding works, it is complex and absorbing. The program for Pacific Currents was both musically enchanting and intellectually demanding, emphasising the impact of rhythm and showing how multiple forms and alternative musical sources could be integrated. All the works use repeated patterns in various ways, showcasing mid-to late-20th-century approaches to composition and the reactions to dominant and avant-garde cultural forms and aesthetics.

The second concert, Wind and Glass, comprised works by two British and three Australian composers. British composer Tansy Davies’ Neon (2004) is based on urgent offbeat rhythms that recall electronic process music, but with more élan and the richer sonorities of miked acoustic instruments. Gavin Bryars’ elegiac The Sinking of the Titanic (1968) is for an ensemble of strings, winds and percussion with a taped voice recalling the event, and the strings performing the hymn, Autumn, that the Titanic’s band was playing as the ship sank. Opening and closing with the sound of tolling bells, the hymn is played by the strings while the rest of the ensemble produces sounds that evoke the ship itself, creating considerable emotional impact. The work has a theatrical feel, with a dialogue between the strings, portraying the final moments of the ship’s orchestra, and the rest of the ensemble.

The concert included the premiere of Brisbane composer John Rodgers’ Glass, a work for chamber ensemble and improvised trumpet developed from the transcription of the sounds created when using a large sheet of glass as a percussion instrument. These sounds were woven into an elaborate composition for the ensemble, and trumpeter Scott Tinkler, for whom Glass was written, improvised in response to the ensemble, creating a scintillating musical interaction. He produced a wondrous range of sounds, from clarion calls to growling and blaring, adding to the profusion of textures and timbres created by the ensemble. A highlight was Brett Dean’s Dream Sequence (2008), a magical work for the full ensemble, wonderfully orchestrated, expressionistic and densely woven, that expands our musical awareness by taking us on a surreal internal journey.

All this prepared us well for the centrepiece of the two concerts, Errki Veltheim’s compelling new work Tract (2009). Commissioned for performance in the festival by the London Sinfonietta and the Young Wägilak Group, Tract is really two pieces of music that coincide—the orchestra performs Veltheim’s score, with Veltheim as violin soloist, while the four-member Young Wägilak Group perform Manikay, traditional songs of their country in North-Eastern Arnhem Land, powerfully sung with clapsticks and didgeridoo accompaniment. The two strands of music progress sometimes together, sometimes separately, with Veltheim linking them with his own playing. In a forum following the concert, Veltheim said that the Manikay operate as a religious text and that he had written a high modernist score that would match the Manikay performance in structure and intensity but would not imitate it. The Young Wägilak Group has previously worked with the Australian Art Orchestra, and, while such collaboration could appear contrived, the result here is a unique and inspiring musical and cultural form. Tract is not a hybrid but rather a cross-cultural dialogue, with Veltheim’s violin as the catalyst, each strand of music acknowledging the functions, traditions and aesthetics of the other. The audience response was overwhelmingly positive.

Some thoughtful programming went into these London Sinfonietta concerts, the second building on the investigative platform established in the first with more radical examples of the simultaneous use of multiple musical forms. The two concerts showcase many ideas: the layering of music through competing rhythms, structures and instrumentation; the reworking of aesthetics that arise from sampling and electronic manipulation; the impact of mechanical and recorded sources of sound, such as phonograph, tape, radio, vibrating glass and piano rolls; and the juxtaposition of disparate musical cultures and traditions. Brett Dean and Unsuk Chin have explored the expressive possibilities of intricate musical structures. The works of Cage and Revueltas show how popular media can generate a musical melange. Bryars has woven his own composition around an existing composition to convey the sentimental impact of an historical moment. Mikhashoff has dazzlingly transformed Nancarrow’s work. And Velthiem has brought two cultures into a thrilling collaboration. The works of Velthiem, Cage, Rodgers and Bryars are challenging and significant experiments that are engaging conceptually and musically, and mark important developments in musical history. The two concerts greatly illuminate the nature of musical development in a globalising world, showing where experimentation can lead and teaching us how to listen more carefully.

2010 Adelaide Festival, The London Sinfonietta, conductor Brad Lubman, with Lisa Moore, Owen Gunnell, Scott Tinkler, Errki Veltheim and the Young Wägilak Group of Ngukurr, Adelaide Town Hall, Feb 27, 28

A review of theatre and dance works in the 2010 Adelaide Festival will appear in RealTime 97 June/July.

RealTime issue #96 April-May 2010 pg. 6

- Interview = https://abc.net.au

- Miscellaneous = https://lifeatanam.wordpress.com

- Miscellaneous = https://facebook.com

- Programme = https://londonsinfonietta.org.uk

- Report = https://realtimearts.net

-

Text = tract_note.md +

- |

-

ABNB

- Video = https://youtube.com

- |

-

alh84001

-

Audio = alh84001_rev.mp3

-

Audio = alh84001_rev.mp3

- |

-

Triptych

-

Audio = triptych.mp3

-

Audio = triptych.mp3

- |

-

Ergosphere

-

Audio = Ergosphere.mp3

-

Audio = Ergosphere.mp3

- |

-

Ersatz

-

Audio = Ersatz.mp3

-

Audio = Ersatz.mp3

- |

-

Ideal and Actual Proportions, Multiplied and Divided

-

Audio = IdealAndActualProportions.mp3

-

Audio = IdealAndActualProportions.mp3

- |

-

Ingress

- |

-

Synechdoche

-

Audio = Synechdoche.mp3

-

Audio = Synechdoche.mp3

-

the uncertainty of predicting one’s fate: prolegomenon 1

-

Audio = the_uncertainty.mp3

- Image = the_uncertainty_01.jpg

- Documentation = https://sabinamaselli.com

- Text = https://sydneycontemporary.com.au

-

Audio = the_uncertainty.mp3

- |

-

Flutter

-

Audio = flutter.mp3

-

Audio = flutter.mp3

- |

-

AMA

- Image = ama_01.jpg

- Image = ama_02.jpg

- Image = ama_03.jpg

- Video = https://vimeo.com

- Documentation = https://sabinamaselli.com

- |

-

anima del mare

-

Audio = anima_del_mare_soundtrack.mp3

- Image = anima_del_mare_01.jpg

- Image = anima_del_mare_02.jpg

- Documentation = https://sabinamaselli.com

-

Audio = anima_del_mare_soundtrack.mp3

-

Fantasia (after J.S. Bach Fantasia in A Minor BWV 922 c.1710)

-

Audio = FantasiaAfterBach_1.mp3

-

Audio = FantasiaAfterBach_2.mp3

-

Audio = FantasiaAfterBach_1.mp3

- |

-

North of North

- Image = north_of_north_cover.jpg

- Audio = https://immediata.bandcamp.com

- Programme = https://melbournerecital.com.au

- |

-

ST/AB/EV

- |

-

The Unpossibility of Language

-

Audio = whose_idea_was_this.mp3

- Image = st_ev_mh_cover.jpg

-

Audio = whose_idea_was_this.mp3

- |

-

MARDI À MONTREUIL

- Image = montreuil_01.jpg

- Label = https://anthonypateras.com

- |

-

Surgical Violin

-

Audio = surgical_violin.mp3

-

Audio = surgical_violin.mp3

- |

-

051111/3

-

Audio = 06_051111_improv_3.mp3

-

Audio = 06_051111_improv_3.mp3

- |

-

061111/3

-

Audio = 061111_3.mp3

-

Text = 061111_3.md +

Erkki Veltheim, PERFORMANCES / IMPROVISATIONS

Astra’s 60th season in 2011 celebrates different facets of our work over the decades. Pieces by 20 Australian composers are heard across the six concerts, but also performances from some of the leading contemporary players whose contributions have always widened the perspective of our choir-based programs. Erkki Veltheim in this concert joins previous performances in 2011 by Genevieve Lacey (recorder), Michael Kieran Harvey (piano), and the group Speak Percussion (Eugene Ughetti, artistic director). A larger ensemble follows, in combination with the Astra Choir, for the final concerts on December 3 and 4 at Northcote Town Hall.

At the same time, this concert represents something new – Erkki Veltheim’s first solo recital on the violin. As a performer, composer, improviser and arranger he is active across an extraordinary range of styles and genres, but is best known in the classical music world as a viola player, appearing internationally with leading groups from Ensemble Modern (Frankfurt) to the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, and in this country from the ensemble Elision to the Australian Chamber Orchestra. For Astra he previously played Elisabeth Lutyens’ solo viola Echo of the Wind at her centenary concert, and in the string quartets of Johanna Beyer for our New World Records CDs. Erkki Veltheim’s increasing work as a violinist has placed him in an onstage role in Brett Dean’s opera Bliss, and as virtuoso improviser in his own composition Tract, commissioned for the Adelaide Festival and overlaying a sound-sculpture for the London Sinfonietta and a traditional song-cycle from Arnhem Land. A regular performer at Australian improvisation events, he is active in an array of rock, gypsy and world music bands, with the indigenous collective Black Arm Band, and as band musician and song-writer for his own group Roadkill Rodeo.

Many musical strands and skills thus flow into today’s concert! – mediating between improvisation, Bach’s classic monument for the instrument, and two solo works by Brisbane-based composer John Rodgers. Himself a violinist of legendary ability, John Rodgers also ranges widely beyond the boundaries of classical music, and has a close association with the Australian Art Orchestra, of which he is a founding member. His noted CD A rose is a rose... combines him with a row of improvising soloists. Today's performances of his challenging violin works are the first by another violinist. The concert also takes the opportunity to re-voice the Astra Improvising Choir, first directed by Joan Pollock in the 1980s. A vocal presence perhaps underlines the hidden chorale singing which recent research has established within Bach's Chaconne, understood by some as a tribute to his first wife on her death. -- JMcC

A couple of months ago I was looking for a venue to put on a concert that would combine a few notated pieces interspersed with improvisations on violin. I wanted to finally play John Rodgers' two solo pieces from his A rose is a rose... record, which are telling of his obsessions at the time; the harmonic language of Elliot Carter, the rhythmic vitality of Indian Carnatic music, and playing violin ridiculously well. Similar obsessions can be heard in John's improvisations, and those of a small community of musicians such as the drummer Ken Edie, John's longtime collaborator, trumpet player Scott Tinkler, and the pianist Marc Hannaford, who have created an improvisatory language with an internal grammar that allows for real musical interplay and communication, yet to me doesn't sound derivative. I thought it would be interesting to combine John's pieces with Bach's Chaconne, a set of variations by another improvising musician, also an obsessive synthesizer of different styles. I was having trouble finding a suitable venue for this concert, so rang John McCaughey to ask him about the Eleventh Hour Theatre, which I heard had a great acoustic for string instruments. A bit of serendipity meant that John was looking to fill a program around the same time, and asked me if I would present this recital under Astra's auspices. This led to the idea of including a piece with the improvising members of the Astra Choir. I thought it would be a fun experiment to try an improvised piece based on the song of the lyrebird, known as the most accomplished mimic of the bird world. This gives the choir free reign to explore a whole range of rainforest sounds from bird-calls to insects, and also comments on the nature of my own creative mimesis; two of my good violinist/composer friends, John Rodgers and the fiddle champion Hollis Taylor, are well known for their own pieces based on birdsong, and it seems like an appropriate homage to some of the integral influences on my musicianship to include one in this concert. -- EV

- Text = 2011_5.pdf

-

Report = 061111_3_rt.md +

tuning the audience

simon charles: erkki veltheim, astra

PRESENTED UNDER THE AUSPICES OF THE ASTRA CHAMBER CHOIR, ERKKI VELTHEIM’S SOLO VIOLIN RECITAL CONTINUED ASTRA’S TRADITION OF EXPLORING THE DRAMATURGY OF MUSICAL PERFORMANCE. THE VIOLINIST APPEARED TO DISREGARD THE CONVENTIONS AND RITUALS USUALLY ASSOCIATED WITH CONCERT PERFORMANCE.

This was obvious from the outset when, in a T-shirt, Veltheim entered the 11th Hour Theatre moments before performance time, unpacked his instrument on stage and immediately began to tune. As the audience continued to chatter, Veltheim’s notes evolved into wider intervals, seemingly testing instrument and acoustic. As this process became more elaborate, Veltheim drew attention away from the conversations in the room, which inevitably petered out, to the improvisation that ensued.

Veltheim’s improvising—far from mere noodling—provoked intense interest. It not only allowed a different route into the performance, but one that bypassed arcane rituals of entrance and applause. The improvisation allowed Veltheim to establish a rapport with the audience and to carve out a space that the first piece of the program, Chaconne from Partita in D minor by JS Bach, could inhabit.

In a more typical setting, Bach’s Chaconne would be used as a means for a player and audience to become more attuned to a space and its acoustic. However, here this end had already been achieved. Continuing in the spirit of improvisation, the performance of the Bach conveyed a sense of spontaneity and exploration, executed with extreme finesse.

Chaconne was followed with more improvisations, which developed uniquely and idiosyncratically. Without restraints, moments of intensity and climax could be measured and gradually worked towards with an ever present and intense energy which delivered a succession of musical statements of remarkable strength and clarity.

Veltheim’s improvisational language is very much reflected in the two works on the program by John Rodgers, also a violinist and improviser of immense ability and a former mentor of Veltheim. Solo for Violin and 1/1/94 both demand what seems to be an unprecedented level of virtuosity and were handled in this performance (the premiere of these works by a violinist other than Rodgers) with breathtaking clarity and focus.

The deliberate avoidance of a traditional concert setting put all focus squarely on the performer, without a shred of pretence to hide behind. There was a brutal honesty in the performance presenting the music in its most essential form.

The stark reality of this performance took a more surreal turn when Veltheim was joined by members of the Astra improvising choir, situated behind the audience and around the perimeter of the room. This ensemble of six singers contributed short gestures of guttural sounds and extended vocal techniques. Having spent the first and greater part of the program listening only to the sound of a solo violin, hearing sounds travel from various locations throughout the space had a refreshing effect.

It is hard to think of any musical organisation in Australia presenting work in the way Astra does. Now in their 60th season, there is a characteristic rigour and integrity in every program, managing to integrate new and innovative work with older repertoire, rather than pandering to a particular taste.

Both Solo for Violin and 1/1/94 are on John Rodger’s excellent recording A Rose is a Rose (XLTD-007 CD 2000; http://www.xtr.com/catalog/XLTD-007).

Violin Erkki Veltheim, Astra improvising choir, Joan Pollock (artistic coordinator), Louisa Billeter, Laila Engle, Susannah Provan, Katie Richardson and Sarah Whitteron, musical director John McCaughey, 11th Hour Theatre, Melbourne, Nov 6, 2011 RealTime issue #107 Feb-March 2012 pg. 40

- Report = https://realtimearts.net

-

Audio = 061111_3.mp3

- |

-

Manductio by Mercedes

-

Audio = 1_big_stick.mp3

-

Audio = 2_puncher.mp3

-

Audio = 3_truck.mp3

-

Audio = 4_german_philosophers.mp3

-

Audio = 5_puncture.mp3

-

Audio = 6_gate_skater.mp3

-

Audio = 7_merc.mp3

-

Audio = 1_big_stick.mp3

- |

- Raw Meat

-

Fusion of Tongues

-

Synopsis = fot_synopsis.md +

Fusion of Tongues installation, Maison Folie, Mons, Belgium.

-

Audio = fot_documentation.mp3

- Image = fot_image.jpg

- Image = fot_0526.jpg

- Image = fot_0539.jpg

- Image = fot_0563.jpg

- Image = fot_0591.jpg

- Image = fot_0509.jpg

- Image = fot_0527.jpg

- Image = fot_0542.jpg

- Image = fot_0570.jpg

- Image = fot_0593.jpg

- Image = fot_0524.jpg

- Image = fot_0532.jpg

- Image = fot_0556.jpg

- Image = fot_0576.jpg

- Image = fot_0603.jpg

- Image = fot_0525.jpg

- Image = fot_0533.jpg

- Image = fot_0558.jpg

- Image = fot_0577.jpg

- Image = fot_0605.jpg

-

Synopsis = fot_synopsis.md +

- |

- lampaanviulu II

- |

-

lampaanviulu I

- Image = lampaanviulu_1.jpg

- Image = lampaanviulu_2.jpg

- Text = https://riikosakkinen.com

- |

-

Efference Copy

-

Audio = EfferenceCopy_installation.mp3

-

Audio = EfferenceCopy_performance.mp3

-

Audio = EfferenceCopy_installation.mp3

-

Partita No. 2 (D Minor)

-

Audio = bach_allemanda_corrente.mp3

-

Audio = bach_ciaccona.mp3

-

Audio = bach_sarabanda_giga.mp3

-

Audio = bach_allemanda_corrente.mp3

- |

-

1/1/94

-

Audio = 061111_jr_1_1_94.mp3

-

Audio = 061111_jr_1_1_94.mp3

- |

-

Solo for violin

-

Audio = 04_051111_jr_solo.mp3

-

Audio = 04_051111_jr_solo.mp3

- |

-

Embellie (1981)

-

Audio = embellie_live.mp3

-

Audio = embellie_live.mp3

- |

-

Inside (1980)

-

Audio = inside_live.mp3

-

Audio = inside_live.mp3

- |

-

Trema (1981)

-

Audio = trema_live.mp3

-

Audio = trema_live.mp3

-

Shit to the spirit

-

Synopsis = synopsis.md +

- Image = img_5630b.jpg

- Image = stts.jpg

-

Synopsis = synopsis.md +

- |

-

Roadkill Rodeo

-

Audio = whisper_your_name.mp3

-

Audio = lifetime_of_tears.mp3

-

Audio = i_came_to_you.mp3

-

Audio = other_peoples_misery.mp3

-

Audio = whisper_your_name.mp3

-

UCSD Solo Violin Recital

- Programme = ucsd_program_front.pdf

- Programme = ucsd_program_front_scan.jpg

-

Programme = ucsd_program_front_ocr.md +

Program notes

In this concert I am presenting works by two Australians with whom I have had long collaborative relationships, John Rodgers (b. 1963) and Anthony Pateras (b. 1979), both who are known equally as composers and improvisers working across a plethora of musical contexts. These works are nestled amongst short solo pieces by composers who have in some ways influenced them, as well as an improvisation with Dr Anthony Burr and a recent work of my own for an improviser and electronics.

John Rodgers' Duet for violin and bass clarinet is informed by the harmonic and rhythmic language of Elliott Carter, as well as his study of the rhythmic structures of South Indian Carnatic music. The two instrumental parts, which can also be performed as separate solo pieces, are written in different tempi; the violin's speed relates to that of the bass clarinet in the ratio of 5:7, creating two independent pulse streams that only meet when the violin plays septuplets to the bass clarinet's quintuplets. Dr Anthony Burr and John Rodgers were close colleagues whilst they were both living in Brisbane, Australia, and this work was originally written for and performed by the two of them. Dr Burr and I have both also worked extensively with Rodgers as improvisers, adapting many of the same musical principles to spontaneously composed music, and it thus seems fitting for us to follow this work with an improvised segment.

I also share a varied and enduring musical dialogue with the Melbourne-born composer and pianist Anthony Pateras, through performances in each other's and other colleagues' projects and most recently in an improvising duo. Pateras has, like Rodgers, been influenced by a diverse group of musicians, artists and thinkers, with Feldman and Xenakis foremost among them. Rules of Extraction, ** his new work for violin and electronics, creates a web of psychoacoustic phenomena through slowly evolving layers of oscillators, also recalling Alvin Lucier's works for solo instruments with sine waves.

Turing Test was inspired by Lydia Goehr's book 'Imaginary Museum of Musical Works', which questions the concept and locus of a 'musical work'; is it contained in ideal form in a notated score, or does it exist only through a concrete performance, or is it the sum total of its performances? And how does a work of music maintain its identity across different performances? Whilst Goehr mainly dicusses examples from the notated classical canon, the basic questions can be naturally extended to improvisation, especially as it is typical in this practice for iterations of the same 'work' to sound extremely different, to the point where recognition of any common, sustained identity across these iterations becomes almost impossible. In response to this book, I became interested in constructing a piece that combines a freely improvised part with a completely automated and structurally predetermined electronic part that processes (and thus requires) this live input, creating an interdependent dialogue between an abstract structure and spontaneous live performance.

- Programme = ucsd_program_back.pdf

- Programme = ucsd_program_back_scan.jpg

-

Programme = ucsd_program_back_ocr.md +

UC SAN DIEGO

DEPARTMENT OF MUSICERKKI VELTHEIM

Tuesday, April 14,2015 11:00am.

Conrad Prebys Concert HallProgram:

Elliott Carter: Statement – Remembering Aaron (1999) for solo violin (from Four Lauds)

John Rodgers: Duet (1995) for violin and bass clarinet

Anthony Burr and Erkki Veltheim: Improvisation

Morton Feldman: For Aaron Copland (1981) for solo violin

Anthony Pateras: Rules of Extraction (2015) for violin and electronics (World premiere)

Iannis Xenakis: Mikka (1971) and Mikka 'S' (1976) for solo violin

Erkki Veltheim: Turing Test (2014) for improviser and electronics

Biography

Erkki Veltheim is a musician and interdisciplinary artist. He has performed as a violinist/violist with ensembles such as the Australian Art Orchestra, Australian Chamber Orchestra, Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, Elision, Ensemble Modern and Ensemble musikFabrik, and has also featured as a soloist with the London Sinfonietta, Melbourne Symphony Orchestra and Opera Australia. As an improviser he has worked with Australia's leading practitioners, including Anthony Pateras, John Rodgers, Jon Rose, Scott Tinkler and Tony Buck, and has also performed with the Dutch drummer Han Bennink and American trumpeter Wadada Leo Smith. Erkki has been commissioned by the Adelaide Festival, Vivid Festival (Sydney) and the New Music Network, and his compositions have been performed by ensembles such as the London Sinfonietta, Melbourne Symphony Orchestra, Soundstream Collective and Sydney Symphony Orchestra. He has also performed with and composed arrangements for artists across various genres, including many prominent indigenous Australian traditional musicians and singer-songwriters. Erkki's interdisciplinary performance and installation works explore the role of sound and music in language, communication, social exchange and ritual, and vice versa, and he frequently collaborates with the artist Sabina Maselli on audiovisual performance and expanded cinema projects. Erkki is an Artistic Associate of Chamber Made Opera, a Melbourne-based contemporary opera company.

UC San Diego

Division of Arts & Humanities

- |

-

Another Other

-

Synopsis = synopsis.md +

<|vimeo,121005699,500:281

-

Report = barmby.md +

Another Other

by David Barmby

A take-no-prisoners ghost-train ride into horrors within.

'A cadaver wrapped in black plastic twitches in the corner like a snake with its head cut off. Ticking erratically, this animated corpse offers a counterpoint to the digital clocks at opposite ends of the space. Facing each other, these clocks mark time passed and time to come.'

Stretching the boundaries of what might be considered opera (there is little singing, theatre or text) Another Other (part experimental opera, expanded cinema, sound art and installation) is a multi-media tour de force rhetorically based on the black and white film, Persona (1966) directed by Ingmar Bergman.

In Bergman’s essay The Snakeskin he describes Art as equivalent to a snakeskin full of ants ‘the snake itself is long since dead, eaten out from within, deprived of its poison: but the skin moves, filled with busy life’. On our way into the theatre we pass the cadaver wrapped in garbage bags and discarded into a corner, with the ‘pluck-plock’ sound of erratically ticking clocks engulfing us. Was this the discarded remains of Western Art we were passing? It foreshadows what is to come in this exceptional creative achievement by Chamber Made Opera, a take-no-prisoners ghost-train ride into horrors within.

The 79-minute Another Other (though it was 90 minutes on opening night) questions the relevance of art forms, ‘authenticity’, our identities and genders. In the vast Meat Market space, the work uses fours screens and 12 microphones with centrally located performers facing each other behind computers and other technology, screened by two ceiling-to-floor gauze screens onto which images are projected. Beyond the centre, the audience sits in two banks of raked seating facing one other. Further screens are to the side and behind each half of the audience.

The program note dscribes the work as “deeply collaborative” with “everything discussed in depth, each scene and our understanding of it”. There is no composer, librettist nor director; rather four voices around a table interacting with one another in a controlled chaos.

So how did it go? Firstly, the lay-out of the project worked very well. To sit looking through two transparent screens of projected image to a further screen and the audience beyond, and to hear multifarious sonic contributions from the artists before us provided a wonderfully rich tapestry of abstraction to behold. Anderson’s improvisations using digitally processed garklein recorders, Veltheim violin contributions (including an excerpt of Bach’s Chaconne from Partita No 2 in startling counterpoint with screened soap opera) and Masselli’s 16mm film contributions were all highly engaging, but it was Pateras’s exquisitely refined and precise sound world of texture and sonority, using a synthesiser and reel-to-reel tape recorder manipulating his own sounds, pre-recorded sounds and those of others, which proved to be the most rewarding aspect of the work. Overall, sitting through 90 minutes of episodic abstract soundscape and film without apparent structure or narrative was not a simple task; I felt that the work might be tightened and it was my instinctive need to have a clearer understanding of form, that I know the work was avoiding, which proved frustrating. In sum: a first-rate undertaking and a highly successful model for future collaboration.

Rating: 4 out of 5 stars

Another Other

Presented by Chamber Made Opera

Thursday, 18 February to Sunday, 21 February at 8pm Meat Market, North Melbourne

Created and performed by:

Natasha Anderson, composer and installation artist

Sabina Maselli, film maker and visual artist

Anthony Pateras, pianist and electro-acoustic musician

Erkki Veltheim, violinist and interdisciplinary artist

Byron Scullin, Production Management/Audio

Jenny Hector, Lighting Design

Marco Cher-Gibard, Technical SupervisionAnother Other was commissioned by Chamber Made Opera with support from the Australia Council for the Arts, Creative Victoria, Sue Kirkham and Charles Davidson.

First published on Friday 19 February, 2016

What the stars mean?

- Five stars: Exceptional, unforgettable, a must see

- Four and a half stars: Excellent, definitely worth seeing

- Four stars: Accomplished and engrossing but not the best of its kind

- Three and a half stars: Good, clever, well made, but not brilliant

- Three stars: Solid, enjoyable, but unremarkable or flawed

- Two and half stars: Neither good nor bad, just adequate

- Two stars: Not without its moments, but ultimately unsuccessful

- One star: Awful, to be avoided

- Zero stars: Genuinely dreadful, bad on every level

About the author

David Barmby is former head of artistic planning of Musica Viva Australia, artistic administrator of Bach 2000 (Melbourne Festival), the Australian National Academy of Music and Melbourne Recital Centre.

-

Report = boon.md +

Review: Another Other (Chamber Made Opera)

by Maxim Boon

February 19, 2016★★½☆☆ This ode to Bergman's masterwork, Persona, is technically virtuosic but ultimately impenetrable.

Meat Market, Melbourne

February 19, 2016There is an inherent conflict in art responding to art; it begs the question, how does the homage react to its source material in a way that is both respectful and yet communicative of a distinct creative voice? Where is the personal authenticity of the artist if they are reimagining someone else's vision? Devising something that can exist in isolation and yet also contributes to the legend of its inspiration is a complex equation to solve, and while Chamber Made Opera's Another Other makes a valiant attempt at decoding Ingmar Bergman's densely layered 1966 masterpiece, Persona, the result is ultimately impenetrable.

Flanking a central hub of mixing desks and laptops, two banks of seats, set opposite each other, are separated by a series of sheer fabric panels. With the four instigators of the piece - Natasha Anderson, Sabina Maselli, Anthony Pateras and Erkki Veltheim - sat between the two hemispheres of this performance space, we are offered a complex geometry of spatially controlled soundscapes and projected images. There are two digital clocks either side of the performers, one counting down, the other marking the passing of time, and on the outer edges of the room, a series of spotlights occasionally dazzle the audience with bursts of blinding light. It's a dizzyingly complex arrangement, easily capable of sensory overload, and largely, that's exactly what it delivers.

Distilled to its most experiential components, everything but the vaguest semblance of Bergman's narrative is discarded. In its place, we are offered a more disjointed pallet of inscrutable references that combine to create a series of episodes mixing film, real-time manipulation of live performance and electronic soundscapes. There is a faint, skeletal presence of Persona's structure, but only as a subliminal afterthought.

Gesturally, there are clearly discernible artefacts from Bergman's tense modernist drama. The lack of spoken dialogue mirrors Bergman's mute protagonist, Elisabet. Then there's the use of found sounds like the whirring clatter of a film projector or the pointillism of dripping water, the use of provocative iconographies, such as Malcolm Browne's famous image of a self-immolating Tibetan monk, and the pointed exposure of the mechanics of the production akin to Bergman's jarring film reel. At one point, a short excerpt of the Chaconne from Bach's Partita No 2 makes an explicit nod to the use of Bach's E Major Violin Concerto in Persona. It's a rich array of ingredients, but somehow they fail to form a cohesive whole.

Another Other achieves from a technical perspective is incredibly impressive. All of its constituent components are coordinated seamlessly, and there is a level of sophistication at work in the realisation of the projections and sound design which is particularly virtuosic. With so much in its arsenal, there could have been a little more restraint in the execution. Almost every part of the elaborate production design is revealed in the first 15 minutes of the show, leaving very little room to increase the intensity or surprise later in the piece.

There is a creative élan at play that speaks to the obviously rewarding collaboration between the four artists who have created this show, as well as the palpable reverence they share for Bergman's film. However, what this production mistranslates is the finesse and narrative subtlety of Persona. Many of the statements this show makes are gratuitously confronting without having any perceptible logic or dramatic momentum to support it, and there is a noticeable dearth of more nuanced moments to offer some counterpoint.

There is also an intellectual elitism present that is perhaps too exclusive. In its attempts to out-compete the cerebral intensity of Persona, Another Other muscles out any of the theatrical potential that would have allowed a more rewarding connection for the audience. I'm not suggesting that eschewing a figurative, traditionally crafted narrative arc is a critical issue, but there is an unignorable implication that a thorough and academic appreciation of the subtexts in Bergman's film is needed to understand what this production is trying to say. I applaud how creatively boisterous this ambitious show is, but in its myopic excitement, Another Other has closed its borders to all but the most informed audience.

**Chamber Made Opera present Another Other at the Meat Market, North Melbourne, until February 21.

-

Report = lanson.md +

Persona re-personified

Klare Lanson, Chamber Made Opera, Another Other

Klare Lanson is a Castlemaine-based writer, poet, performance maker and sound artist. Her project #wanderingcloud (RT118, p41) is to premiere at the upcoming Castlemaine State Festival (http://castlemainefestival.com.au/2015/event/wanderingcloud/).

Another Other, Chamber Made Opera, photo Christie Stott and Josh BurnsChamber Made Opera's Another Other, produced in collaboration with Punctum and New Music Network, is a new work created and performed by Erkki Veltheim, Sabina Maselli, Natasha Anderson and Anthony Pateras, a stunning audiovisual renewal of filmmaker Ingmar Bergman's legacy.

In “The Snakeskin,” an essay written in 1965, Bergman sees art as hunger, pessimistically describing it as a dead snakeskin full of ants, eaten from the inside but still moving with systematic, uneasy activity. A year later Bergman released his seminal film Persona, in which he explored the validity of art, authenticity and the transformative aspects of self.

Another Other probes these themes with expertise and loyalty, a contemporary exploration of our digital age, which enables various online selves, our gaming skins and the smiling veneer of busy loneliness that they project.

Entering the ICU performance space—aptly a dark hospital basement—we see an indistinct black plastic sculptural object, inside which is something sonic and kinetic, rhythmic in its disconnection and obscurity. We are seated on opposing banks, projection screens a mask between audience and performers. The performers' stillness emphasises their geometric positioning. Vocal sighs initiate the score, evoking Persona character Elisabet's feelings of shock as she spirals into silence. Two clocks loom above the performers, activated simultaneously. One counts down, alluding to anticipation, while the other counts upwards, indicating time yet to come. There is continual, circular referencing of the film, repurposed and displaced.

A phone rings. Echoing footsteps walk slowly to one side of the audience. The lights shift; we are spotlit. Alongside the performers we become Bergman's ants in the flaking remnant of snakeskin that here is theatre.

Five video projections come into play throughout in front of the audience and on the walls behind. A 16mm projector stands alone, an antiquated sculptural object; it could be a ready-made. Sabina Maselli handles live visual mixing with ease, driving imagery at different speeds, generating abstraction and re-imagining old film footage. Saturated and hallucinogenic, a mixture of processed and real, it's all a blur.

The acoustic score is both measured and random. Natasha Anderson shifts air through the wooden flaps of an elongated Bavarian recorder, often using the mouthpiece for extended voice work. She plays it as a multipurpose object, hitting, spitting and blowing, her action fractured and magnificent.

Another Other, Chamber Made Opera, photo Christie Stott and Josh BurnsLoops of sound rise and suddenly there are simultaneous projections. A discordant violin twists and turns as a facial close-up is revealed. Colour saturated images shift to black and white and slowly the film disintegrates before our very eyes as it did in Persona (1966). It peels away from the edges, revealing soft white insides. I'm aware of the other half of the audience peering through.

Erkki Veltheim plays remarkable violin, oscillating between exquisitely slow tonal bowing and high-pitched dissonance. He also plays out the most overt reference to the film—the retelling of the sunbaking scene as a spoken word piece. While it doesn't sit well within the entirety of the work, there is an interesting gender switch as he tells the female story of voyeurism, of sexual experimentation of youth and the violent impact that the experience has on the woman's identity. The female vocals become a choral undertone and combine with the imagery to intensify the sense of psychosis.

Anthony Pateras is an astonishing improviser. For Another Other he plays electronics and reel-to-reel tape, altering time and voice. Pre-recorded sound and intense processing generates severity in the score. Pateras is masterful and foreboding as always, an embodiment of storm. The resonating bass takes over, travelling through the body with a harshness that relates to the slapping sounds of the recorder.

The lighting of the audience shifts, creating a new perspective. The clocks now tell the same time, becoming a place of sonic and visual rest. There is silence and then a minimalist sound work begins. It has an oceanic quality, perhaps recalling the beach scenes in Persona.

Images of droplets form and Sabina Maselli stands to operate the projector, turning the cogs by hand, forwards and back, place-making in time.

Another Other is a riveting and fragmented series of micro movements, collectively composed to merge filmic and musical elements just as characters' identities merge in Bergman's film. This hyper-expanded cinematic experience shows our mental life to be a complicated mesh of meaning, open to interpretation.

Like the ego, Another Other is impossible to unpack methodically; there's no narrative thread. This courageous and bold artwork feasts on the art of Persona before the clocks stop and finally there is silence inside the self.

Chamber Made Opera with Punctum and New Music Network, Another Other, creators, performers Erkki Veltheim, Sabina Maselli, Natasha Anderson, Anthony Pateras; Punctum's ICU, Castlemaine, 5, 7 Dec, 2014

RealTime issue #125 Feb-March 2015 pg. 41

-

Report = lorenzon.md +

Partial Durations

A collaboration between RealTime Arts and Matthew Lorenzon.Another Other: A self-fulfilling prophecy about the death of art

February 21, 2016

Erkki Veltheim, Sabina Maselli, Natasha Anderson and Anthony Pateras in Another Other. Photo by Jeff Busby

Waiting in line at the North Melbourne Meat Market, I spot the corpse. A humanoid shape lies wrapped in black plastic bags. The sound of clocks (or are they shovels?) emanate from it. A program essay by Ben Byrne tells us it is the body of art. He quotes Ingmar Bergman (The Snakeskin, 1965) who claims that art is basically unimportant, deprived of its traditional social value. Like a snakeskin full of ants, art is convulsed with the efforts of millions of individual artists. Each artist, including Bergman himself, is elbowing the others "in selfish fellowship," in pursuit of their own insatiable curiosity. To celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of Bergman's film Persona, Natasha Anderson, Sabina Maselli, Anthony Pateras, and Erkki Veltheim have crawled inside the film's 79-minute skin.

The four artists sit facing each other beneath red digital clocks counting down the opera's duration. Pateras works his Revox B77: a machine with a loop of tape and multiple heads that can be manipulated live to produce a stunning array of sounds. Veltheim nurses his violin, which he processes through a laptop running MaxMSP. Natasha Anderson festoons her Paetzold contrabass recorder with an array of sensors and microphones. Sabina Maselli commands an arsenal of projectors and spotlights, including reels of custom-shot 16mm film.

Once inside the film's skin, the collaborators throw out its organs of character and plot. The artists instead motivate its mise-en-scène. Maselli's deeply-textured footage of hands, faces, and landscapes mirror Bergman's own sumptuous images. The close-miked sounds of violin, recorder, and water echo the conspicuous detail of 1960s foley. Spoken text references monologues in the film, notably Alma's story of a foursome on a beach. And so the ideas cycle: hands—faces—landscapes—text, interspersed with solo episodes for each performer, until the time runs out.

Comparing hands. Don't they know it's bad luck? Photo by Jeff Busby

After the third extended shot of intertwined hands, I wondered whether the artists were labouring under a category mistake. Texture and materiality were the bread and butter of contemporary arts throughout the 1980s and 1990s, but the structures of plot and character are surely now considered as much part of the artistic "surface" than image and sound. Thanks to the fashion of basing new music on old films, there are counterexamples. For instance, Alex Garsden's Messages to Erice I & II, which uses the familial relationships of the characters in Víctor Erice's 1973 film El Spíritu del Colmena to structure the algorithmic relationships of four amplified tam-tams.

By throwing out plot and character, the creators of Another Other struggle to address the original film's themes of identity, motherhood, art, and being. The film's iconic shot of Elisabet and Alma's juxtaposed faces is critical of traditional gender roles precisely because the characters struggle with those roles. The repeated superimposition of the artists' faces in Another Other is less critical than narcissistic.

While stating that art's traditional social function is dead, Bergman's essay affirms the personal significance of art, a belief that is reflected in Elisabet's first scene in Persona. Elisabet is an actress who stops speaking because she harbours a burning will to live authentically and shake off the role of motherhood. She laughs at a radio soap but seems affected by a piece of music. In Another Other no such distinction is made between inauthentic and personally authentic art. Veltheim plays the Chaconne from J.S. Bach's violin Partita no. 2 while the artists' faces are shown through a day-time soap vaseline lens. I will accept that universally authentic art is impossible, but I struggled to find even an affirmation of personally authentic art in Another Other. Unsure of the artists' belief in their own work, I failed to commit as an audience member.

After fifty minutes I even started believing that art was dead. Thanks to the clocks high above the stage I could regret every minute left. The saddest thing was that I respect the work of each artist in their own right. But four good artists in a box does not an opera make. At the end of Another Other the artists imagine a different ending to the film. The doctor says that Elisabet's silence was just another role that she sloughed off in the end, not a real existential crisis. She was perhaps also depressed and infantile. The doctor concludes "But perhaps you have to be infantile to be an artist in an age such as this." I laughed. It made me particularly glad I trusted them with an hour and a half of my life.

*Another Other\

- Chamber Made Opera

Meat Market

18 February 2016

Natasha Anderson, Sabina Maselli, Anthony Pateras, Erkki Veltheim.

- Chamber Made Opera

-

Report = owen.md +

Another Other review: Stripped-back, sensuous adaptation of Ingmar Bergman's Persona

Owen Richardson

Published: February 19, 2016 - 8:13PMTHEATRE

ANOTHER OTHER

★★★★

Chamber Made Opera, Meat Market

Until February 21It has been 50 years since the release of Persona, Ingmar Bergman's movie about a famous actress who decides to stop speaking and the nurse who cares for her, about the breakdown and melding of identity, the conflict between inner and outer self and how personality is always a performance.

In recent years we have seen Fraught Outfit's lauded staging of the screenplay and now comes Chamber Made Opera's multimedia performance piece, which excises almost all the words, narrative and characters, leaving behind an absorbing, thoughtful, and crisply performed fantasia on the film's aural and visual textures. Even if the piece's aesthetic is one of interruption and repetition and disjunction, the structure of the film is still discernible, but the sensuousness of the experience is what is most valuable.

The performers – Natasha Anderson, Sabina Maselli, Anthony Pateras and Erkki Veltheim – sit between two banks of seats, separated from the audience by semi-transparent screens: there are also screens behind the seats and to one side. On the screens, superimposed and reversed, pass images of rocky landscapes, intertwined hands, close-ups of lips: the iconic double portraits of Bibi Andersson and Liv Ullmann are recreated, the film's invocation of atrocity – the self-immolating monk – reproduced directly and also updated with the famous falling man of 9/11.

Bergman exposed the apparatus, showing us the camera, the film itself catching on fire, the arc lights in the projector; and conspicuous on stage is a projector-like something from a 1970s school. The noise it makes forms part of a soundscape that elsewhere riffs off the film's jagged music and island setting: glassy percussive sounds, a slashing violin, dripping and bubbling water, bells and a fog horn.

Language barely enters into it: nurse Alma's graphic sex monologue, about a beach orgy with a couple of teenage boys, becomes an even more explicit, Tsiolkas-like episode from contemporary suburban life; and in conclusion a performer reads the speech made by the psychiatrist at the end of the movie: "One must be infantile to be an artist in our age." If true, Another Other disguises it very well.

-

Report = stephens.md +

Another other, reinventing Ingmar Bergman's film Persona by Chamber Made Opera

In an age of multiple identities, a new work draws on Ingmar Bergman to question ideas about who we are, writes Andrew Stephens.

by Andrew Stephens

In an essay he wrote almost 50 years ago, Swedish film director Ingmar Bergman compared art to a discarded snakeskin full of marauding ants – the empty shell of a dead and once-dangerous creature animated by busy scavengers. This was the man who made Persona (1966), the entrancing and intense classic beloved by art-cinema enthusiasts – a film that questioned the very idea of us having fixed personalities or egos.

In a basement performance space in an old country hospital, a quartet of Chamber Made Opera performers have been immersing themselves in both the film and the essay, The Snakeskin, making their own creative, challenging response to them. In effect, what they are sewing together is like another sort of snakeskin layered over the top of Bergman's work.